In the realm of contemporary art, few figures loom as large as Andy Warhol. His signature silver hair, iconic screen prints, and deep fascination with consumer culture transformed him into an enigmatic force that shaped not only the art world but modern culture itself. Warhol’s art wasn’t merely a reflection of his time; it was a profound commentary on how society’s obsession with celebrity, consumerism, and media was changing everything, from How we perceive art to How we live our lives.

Warhol once said, “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes,” a statement that resonates even more profoundly in today’s era of social media and fleeting viral fame. To truly understand Warhol and his art, join Glam/Amour as we dive deep into the mind of a man who blurred the lines between art and commerce, fame and anonymity, and high culture and lowbrow kitsch.

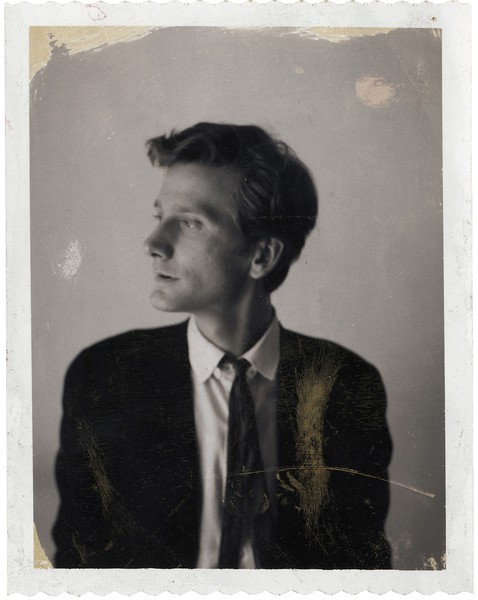

Warhol’s Early Beginnings: From Pittsburgh to Pop Icon

Born Andrew Warhola in 1928 to Slovakian immigrants in Pittsburgh, Warhol’s early life was far removed from the glitz and glamour that would later define him. His humble beginnings in an industrial city didn’t hint at the meteoric rise he would experience. Yet, his love for art developed early on, as he would spend hours sketching and coloring, often bedridden due to illness. Warhol’s mother, Julia, recognized her son’s artistic talent and nurtured it, offering him encouragement in an otherwise bleak environment.

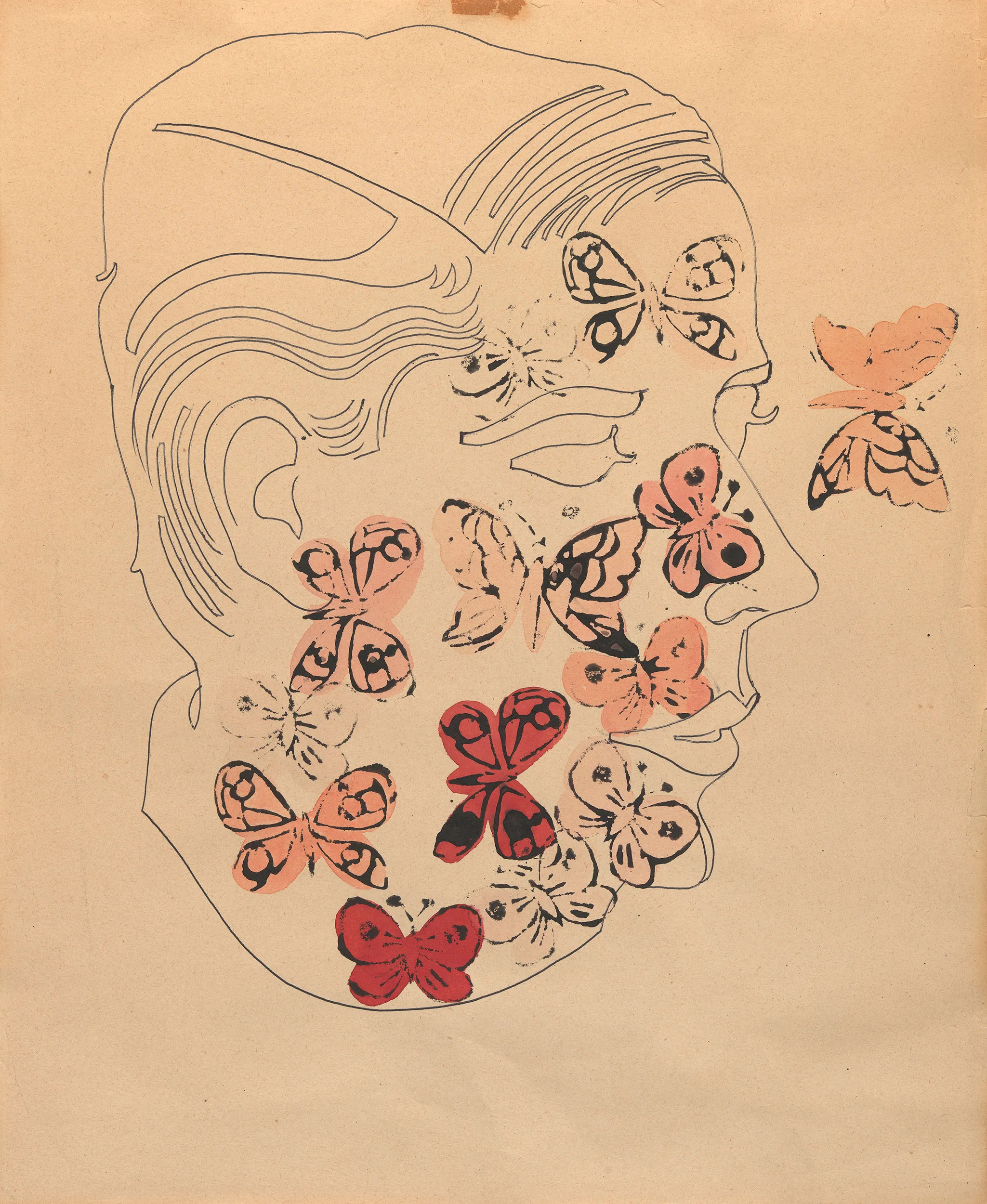

Warhol later moved to New York in 1949 after studying pictorial design at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. Here, he worked as a commercial illustrator, which laid the foundation for his unique approach to art. His work in advertising and magazine illustration honed his skills and made him deeply aware of the visual power of consumerism. This commercial background would soon influence his transition to fine art, where Warhol would revolutionize not only what art could be but who it could speak to.

The Birth of Pop Art: Consumerism as a Canvas

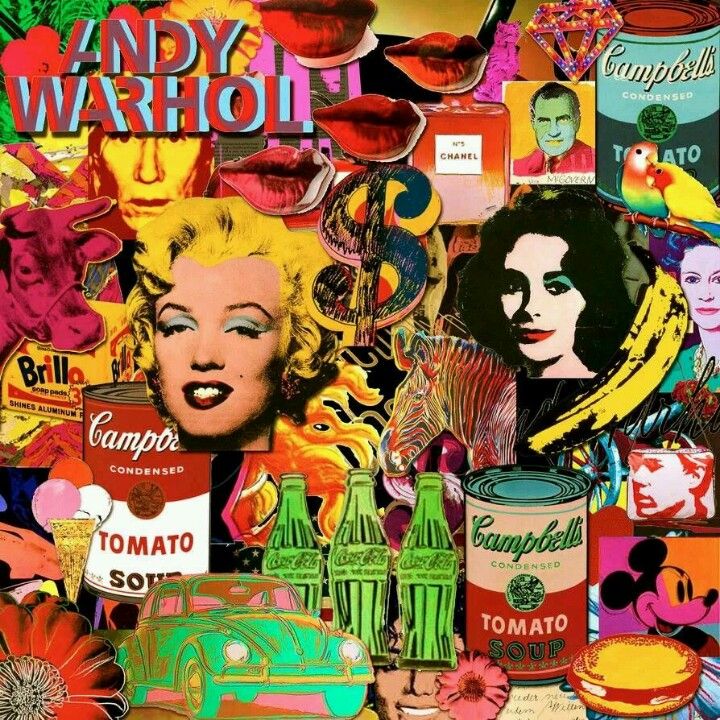

In the early 1960s, Warhol exploded onto the art scene with a new, bold style that would forever change the landscape of contemporary art: Pop Art. His paintings of Campbell’s Soup Cans and Coca-Cola bottles became symbols of this movement, bridging the gap between commercial imagery and high art. Warhol’s decision to use mundane, everyday objects as his subjects was radical. Instead of romantic landscapes or emotional portraits, he painted soup cans—things people consumed without thought, items that lived on grocery store shelves rather than in the grand halls of museums.

Pop Art was a rebellion against the established conventions of what art was supposed to be. At the time, Abstract Expressionism was the dominant force in the art world, with artists like Jackson Pollock splattering paint in a frenzied expression of emotion. Warhol, on the other hand, took the opposite approach. His works were mechanical, repetitive, and devoid of emotion, reflecting the monotonous nature of consumerism.

For Warhol, art wasn’t about expressing the depths of the soul—it was about holding a mirror to society. He famously said, “Pop Art is about liking things.” He didn’t present his objects with irony or critique; he simply reproduced them, elevating consumer culture to the status of fine art. His Campbell’s Soup Cans series became a groundbreaking moment in the art world, asking viewers to reconsider the beauty and meaning in the things they see every day.

Celebrity Obsession: The Art of Fame

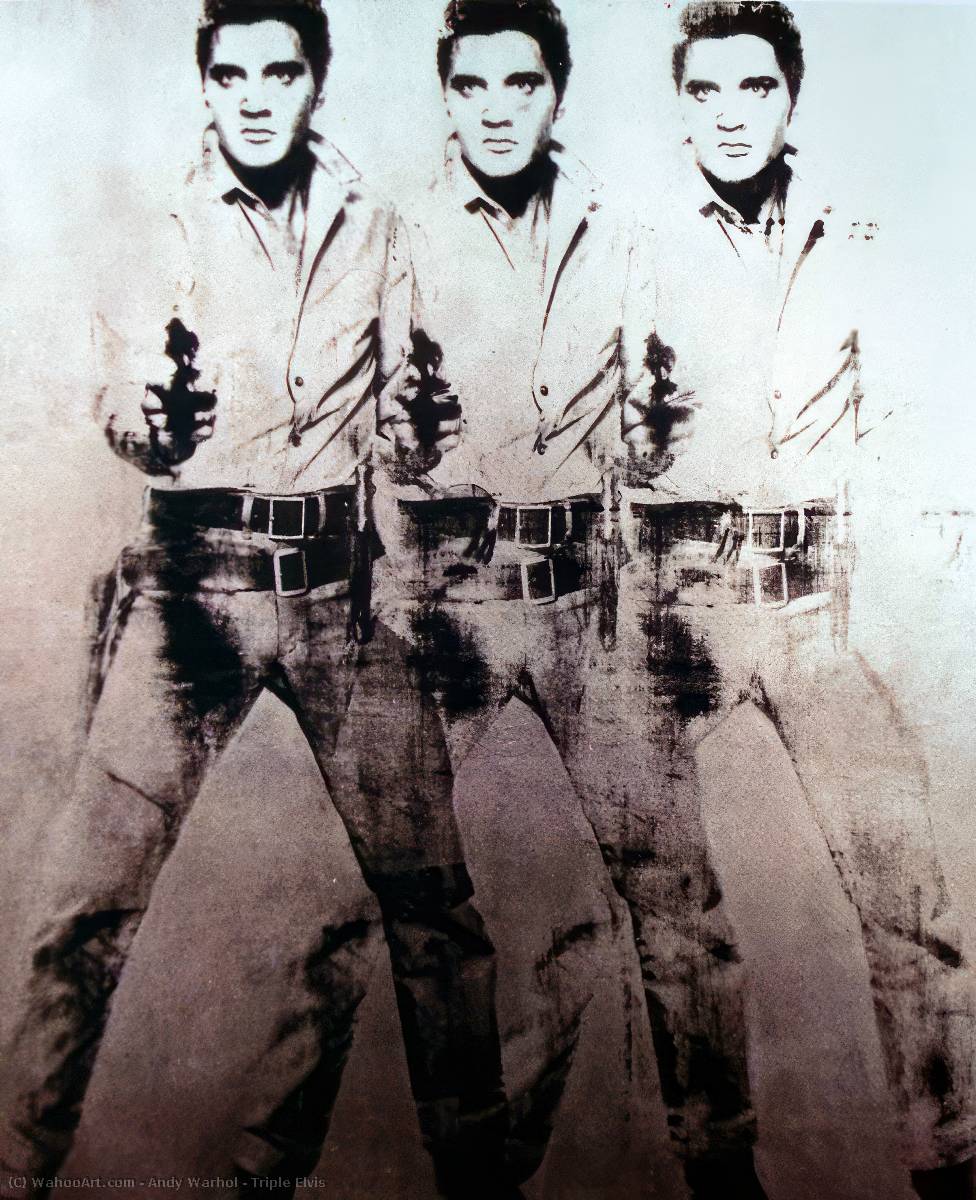

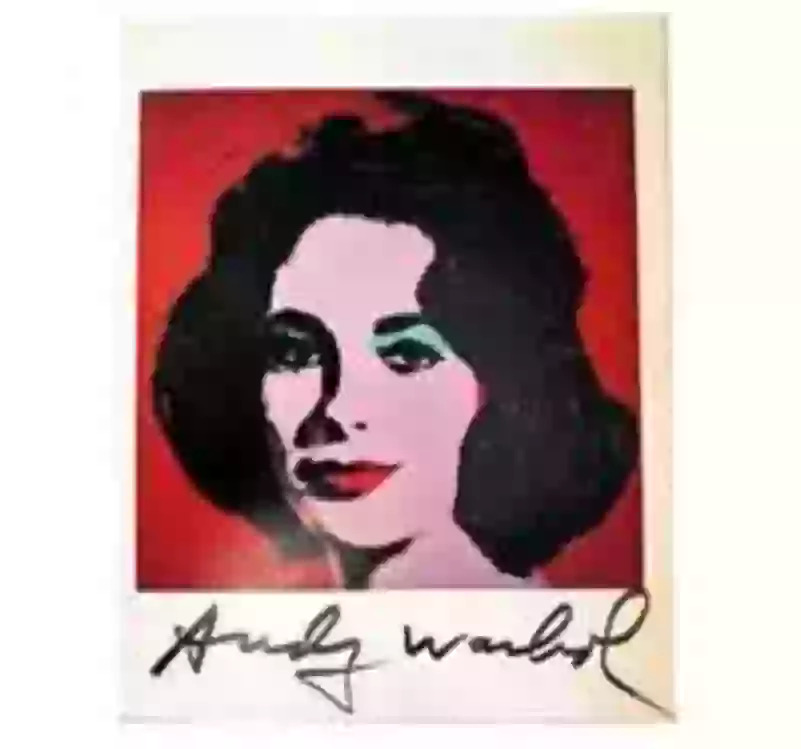

Beyond consumer products, Warhol’s other great obsession was Fame. In a way, Warhol was as much a celebrity as the people he painted. His portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and Elizabeth Taylor are some of the most iconic works of the 20th century. But Warhol’s interest in celebrities wasn’t just about their beauty or talent—it was about the fleeting, fragile nature of fame itself.

The Marilyn Diptych, created shortly after Monroe’s tragic death in 1962, perfectly encapsulates this idea. By using the same publicity still of Monroe over and over, Warhol played with the concept of repetition, suggesting that fame is something manufactured, commodified, and, ultimately, disposable. As the image is repeated, it fades and deteriorates, much like Monroe’s life under the constant spotlight. This work speaks to the dark side of celebrity culture—how stars are consumed by the public until they are worn out and discarded, a theme that has only intensified in today’s media-saturated world.

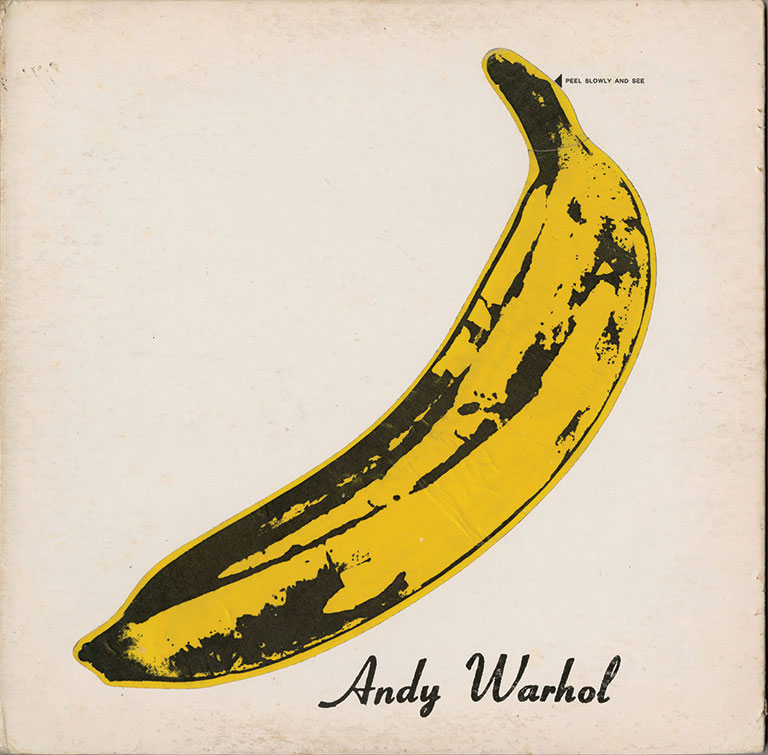

Warhol was fascinated by how the media and advertising turned people into products. In the same way that a soup can could be mass-produced, so could celebrity images. His silkscreen technique further emphasized this point. By using a process that allowed for the reproduction of an image over and over, Warhol eliminated the uniqueness of traditional art. A Warhol wasn’t just a painting—it was a product, just like the celebrities he portrayed.

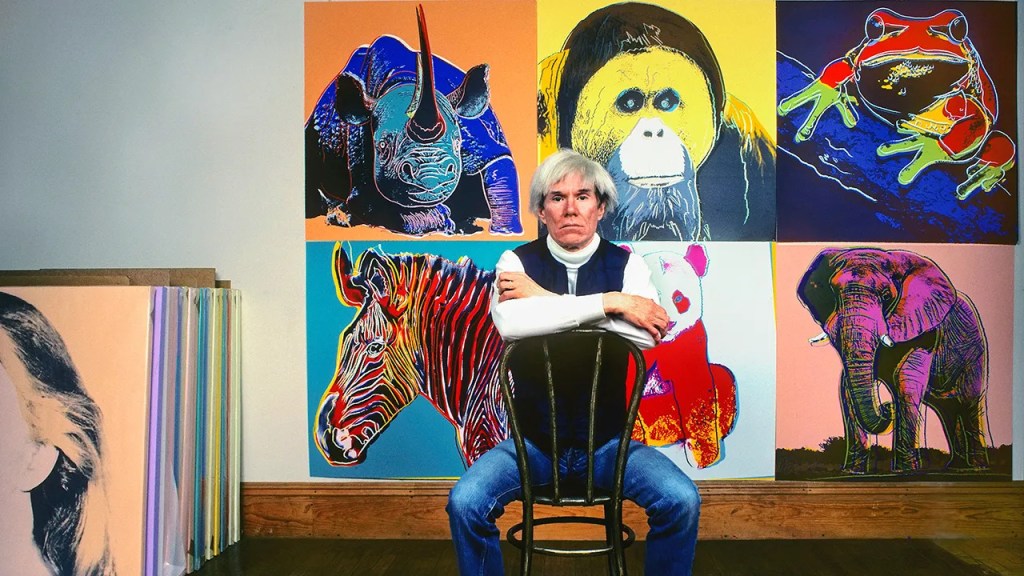

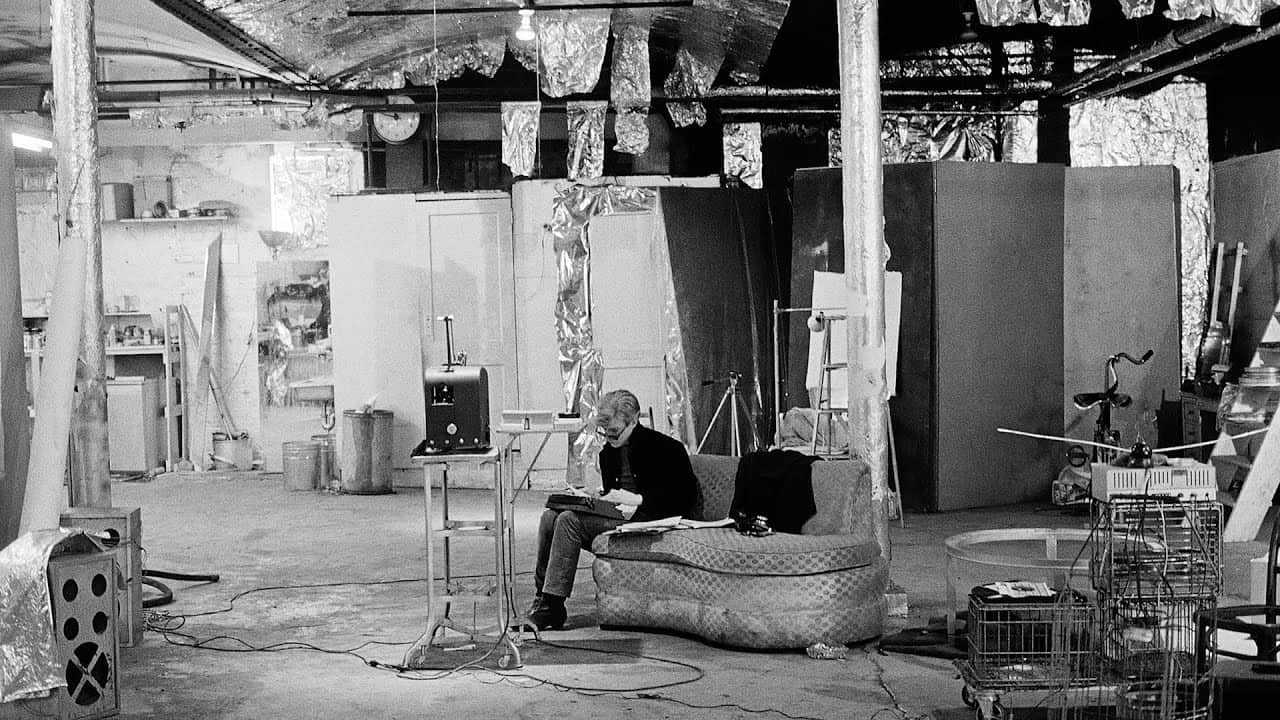

Warhol’s Factory: The Heart of His Creative Empire

At the core of Warhol’s artistic world was The Factory, his infamous studio in New York City. But The Factory was more than just a workspace—it was a social hub, a laboratory for creativity, and a haven for misfits, rebels, and innovators. It was here that Warhol produced his iconic silkscreen paintings, but it was also where he dabbled in filmmaking, performance art, and multimedia projects. The Factory was a reflection of Warhol’s multidisciplinary approach to art, blending high and low culture, celebrity, and everyday life.

Warhol’s films, like Chelsea Girls and Sleep, were just as radical as his visual art. Long, meandering, and often without a clear narrative, these films broke every rule of traditional cinema. Warhol wasn’t interested in telling a story; he was interested in capturing the raw, unfiltered essence of life. His subjects—many of whom were his Factory “superstars,” like Edie Sedgwick and Nico—became part of his living art, further blurring the lines between reality and performance.

But The Factory wasn’t just a place of creativity—it was also a microcosm of the New York avant-garde scene, where artists, musicians, and socialites mingled in an atmosphere of experimentation. Warhol reveled in the role of the observer, watching as the chaos unfolded around him, turning his life into one continuous piece of performance art.

Warhol’s Enduring Impact: More Than Just Pop Art

In 1987, Warhol passed away after complications from gallbladder surgery, but his legacy remains alive and well. His work continues to inspire artists, designers, and cultural commentators alike. Exhibitions of his work, like the recent one in Dubai, draw massive crowds, proving that Warhol’s fascination with consumerism, fame, and mass media is as relevant as ever.

Warhol once famously quipped, “Art is what you can get away with.” But perhaps the true genius of Warhol is that he didn’t just get away with it—he changed art forever.

Through his lens, we can see how deeply our lives are intertwined with the images we consume, the products we buy, and the fame we chase.

In that sense, Andy Warhol wasn’t just an artist—he was a mirror, reflecting the world back at us in all its glittering, mass-produced, celebrity-obsessed glory.

Hope you liked the article! Let us know what you think!